Primitive Nushagak

Right from the outset I am forced to admit failure. The third week of June 2000, I traveled to Alaska intent of piercing the heart of the chinook salmon run on Bristol Bay. Although salmon refuse to adhere to a strict schedule from year to year, given the testimony of locals it was not unreasonable to expect that during late June the chinook run would be nearing full swing.

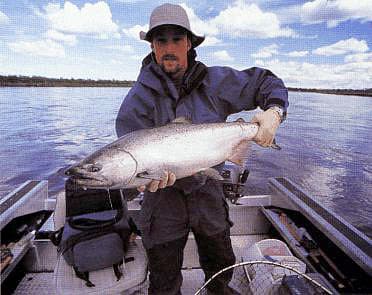

Don’t worry; this will not degenerate into a tale of woe wherein the reader must suffer my humiliations. I and my fellow anglers did intercept the run, though not at its peak, and I caught plenty of fish, more than some of the numbers touted in the more cheesy brochures. In fact, the waxed freezer carton (emblematic of Alaska sporting endeavors) that I checked in at the airline counter prior to departure thunked down so resoundingly on the baggage scale that the ticketing agent curled her lip and growled, “Whaddya got in there, bricks?”

No, the failure to which I allude had to do with my original choice of weapons. My primary goal was to hook a terrible-tempered chinook on a fly. I knew this was within the realm of possibility because of all the places on this water-streaked planet, none could compare with the Nushagak River, harboring the largest king salmon run in Alaska. An instream sonar station on the lower Nushagak accurately records escapement-the number of adult salmon entering the system each season. Although the overall yearly average for the Nushagak is 80,000 fish, there have been years when the population spiked to over 150,000.

As we flew low in the Grumman Goose following the course of the river where it meandered through the tundra, I was both intimidated and dismayed by the size and color of the Nushagak. An unvarying sheet of water 200-300 yards wide, the river flowed as seamless and flat and opaque as linoleum. Big is one thing, muddy is another. As soon as we landed at Alaska King Salmon Adventures, the farthest upriver camp on the Nushagak, we were informed by the owner/guides Bret Brown and Jeff Boggs that we had just missed one helluva rainstorm, the effects of which were quite obvious: brown murk, eroding banks, trees rolling by. But the odd thing was neither Brown nor Boggs seemed the least bit perturbed.

We stored our stuff in Weatherport tents, quonset huts constructed from aluminum pipe and hypalon fabric. Then we bolted down lunch and immediately went fishing. The flood? What flood? Jeff Boggs, our assigned guide for the week, scurried around as if it didn’t matter, as if the willows and Sitka spruce floating by were just part of the scenery. My boat companions included two staff members from G. Loomis Rod Company and an outdoor writer/magazine editor from the Great Lakes. Added up among us, our combined total of salmon fishing experience was about 100 years. Yet, as we were about to learn, compared to Brown and Boggs we were mere dabblers, rank rookies. There’s a big difference between targeting salmon a week or two each year and fishing intensely from dawn to dusk every day for the entire season.

Depending upon the region- whether from northern California to Alaska or from Russia to part of Asia- salmon are known in the varying local vernacular as tyee (a Native word meaning chief), kings, blackmouths, hookbills, smileys, and hogs. Among tribes in Alaska they are known as quinnats. The ancient Ainu in Japan both accurately and poetically referred to salmon as the “present form of heaven.” There’s no arguing with the lore of a fish that can tip the scales at 100 pounds, that can forage in the depths of the open ocean for three to seven years and then unerringly navigate thousands of miles back to the gravel beds of its birth. Adding to the mystery- not to mentions the compulsion of almost a million sport anglers annually- is the fact that salmon eat little, if anything, during the arduous migration home.

Although migrating salmon are disinclined to seek sustenance, feeding instead upon inner reserves, they occasionally fall for a trespassing lure or bait. Jeff Boggs thinks that it’s a result of a “deeply ingrained memory circuit,” a predatory response which triggers more or less automatically when the fish has been sufficiently aroused or irritated. Given the dizzying array of lures glittering on sport shop shelves, the trick is to distinguish between what might be truly provocative and what’s just applesauce.

A diving plug decked out as prescribed on three levels: the visual, the nasal and the aural. Because salmon are both bottom huggers and quite nearsighted, capable of seeing little beyond three feet in front of them, a large flashy plug stands the best chance of getting the fish’s attention. The salmon’s second (if not first) most important sense is probably smell. Lab tests have shown that salmon can detect dissolved substances in concentrations as low as one part per 100 million. Besides masking human scent, sardine oil enhances the salmon’s already keen smell-o-vision. Finally, there’s the disturbance factor. A big plug throbbing through the water emits low-frequency vibrations- subtle auditory signals that are picked up by receptors along the salmon’s lateral line.

We encountered pulses of fish moving upriver and managed to hook chinook here and there, plus a fair bounty of nickel-bright, deep bodied, surprising bellicose chum. By mid- to late-July the species smorgasbord on the Nushagak would include a few thousand coho and about 300,000 (give or take 10,000 or so sockeye). From mid-season on, the cumulative number of salmon congregating in the system exceeds half-a-million fish.

During June in Alaska the sun sets half-heartedly at best, around midnight and comes up again at about three a.m. In other words, it never gets entirely dark and one could, if so inclined, fish until his knees buckled and he was reduced to a mad stare and monosyllabic muttering. The foursome in my boat didn’t go quite that far, opting instead for discrete three to four-hour sessions morning, afternoon, and evening.

The weather firmed up day by day and the river dropped into shape. And either we were able to find more and more salmon in the gradually clearing flows or more and more salmon were able to find us- our lures that is. We didn’t rack up obscene body counts but we did hook- and for the most part release- with a regularity undreamed of in the lower 48.

At the end of day four a bitter wind shrieked inland from the Bering Sea. We huddled in the Weatherport mess tent, slurping coffee and lamenting the unabated winds as the kiss of death. Jeff Boggs, to the contrary, seemed not only unconcerned but positively contented. Boggs explained that the 20-foot-plus tides at night, in concert with a waning moon and strong upriver wind, would almost certainly push a wave of fish out of the estuary and into the Nushagak. Not since the early “60s had Bob Dylan’s slightly vacuous refrain, “the answer is blowin’ in the wind,” come so close to being right.

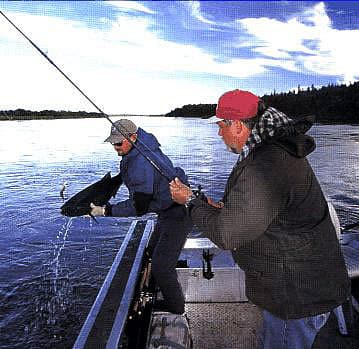

With conditions tilting in our favor we switched from plugs to drift gear. The motivation for change was twofold. First and foremost, Boggs reasoned that with the appearance of competing boats from other camps having followed the fun upriver, and all sticking to the plug program, it made sense to show the fish something different. Furthermore, it was time to wake up his clients as well as the fish. Except for the boatman, who by virtue of constantly positioning the boat is the one really doing the fishing, plugging is a passive sport. Drift fishing, on the other hand, is more skill driven, requiring sensitivity and “connectedness” and, yes, even a modicum of coordination.

The beauty of the Nushagak, despite its daunting breadth and merciless four to eight mile-per-hour current, lies in its long, long cobblestone riffles which skirt seams and bridge pools, where it’s possible to make an extended drift presentation, bouncing bottom unimpeded for hundreds of yards at a crack. With four rods fanned out from the bow we raked the water with the cold efficiency of a navy minesweeper. Par for the course, Boggs had brought to bear the same ilk of fussy refinement in the preparation of our bait rigs as that which distinguished all the terminal tackle and, indeed the operation of the boats and camp as well.

Naturally, the eggs were delivered farm fresh each day via card-punched salmon. A cluster of eggs about the size of a goldfinch was cut from the skein and secured, via an egg loop, to the upper hook in an arrangement of tandem snelled, red-anodized Gamakatsu hooks, separated by a peach corky. A barrel swivel was used to attach four feet of 20-pound test leader to the 30-pound line. To complete the rig a heavy duty slinky, filled with No. 2 buck shot, was fastened to a free sliding swivel threaded on the line above the barrel swivel. Over the remaining day-and-half not only did a number of chinook and chum fall prey to the “egg platter special” but so did native rainbow trout and fat, greedy grayling.

At midday on June 25, as we stacked bulging duffels on the bank prior to departure, a tribal boat swerved into the slack water in front of camp. It brought news of fish on the way, of how “everyone, every man-jack down at Portage Creek” 30 miles downriver was “hooked up” as he motored by. I stared into the river, into six feet of ether-clear water into imminently fly fishable water. In the wake of an embarrassment of riches- more salmon than I could hope to catch in a year back home-it seemed unworthy to complain. But I have to admit, as regards to my unsated fly rod, I was chagrined to be leaving just as a veritable wall of salmon was arriving. (I later called the Alaska Department of Fish and Game to get the daily sonar count: on June 25 over 8000 chinook surged into the Nushagak.)

As so often happens in Alaska, the act of leaving- always a graceless ordeal- was completely overshadowed by thoughts of coming back.

Salmon Academy

One would be hard pressed to find a more engaging, better organized fishing camp than Alaska King Salmon Adventures. Bret Brown and Jeff Boggs, the sultans of slam (as in slamming salmon) have put together a “rough it in style” operation, where you may opt to either fish until you hurt, or more rationally, relax and catch salmon in equal measure. Regardless of your level of angling acumen, fishing with these guys is guaranteed to add fresh script to your angling playbook.

If you have questions about specific salmon fishing techniques, equipment or terminal tackle, call Jeff Boggs at Auburn Sports, (253) 833-1440.

Author Don Roberts lives in Lake Oswego, Oregon

where he launches his many western angling adventures.